Economist’s Corner – Women’s History Month

Women in the Pandemic Labor Market

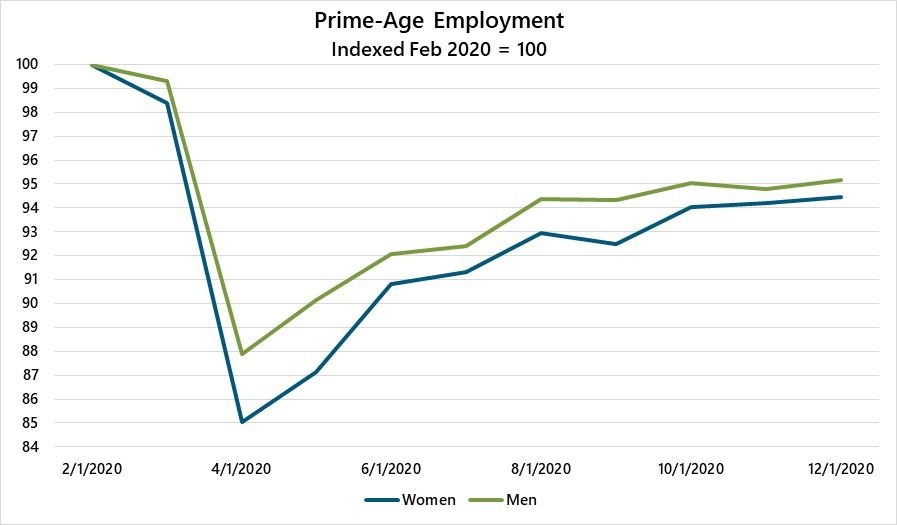

The pandemic has significantly decreased labor demand. From the outset of the pandemic through the end of 2020, prime-age employment (employment among people aged 25-54) fell by approximately five million jobs. The rate of job loss has had disproportionate impacts on women. In this age group, employment through December fell by 4.6 percent[1] for men and 5.7 percent for women. The chart below depicts the path of prime-age employment for men and women from February through December. It shows employment in the first two months of the pandemic fell much more for prime-age women (-15%) than men (-12%). Since then, the rate of employment growth for prime-age women has outpaced that of men, but the employment gender gap remains.

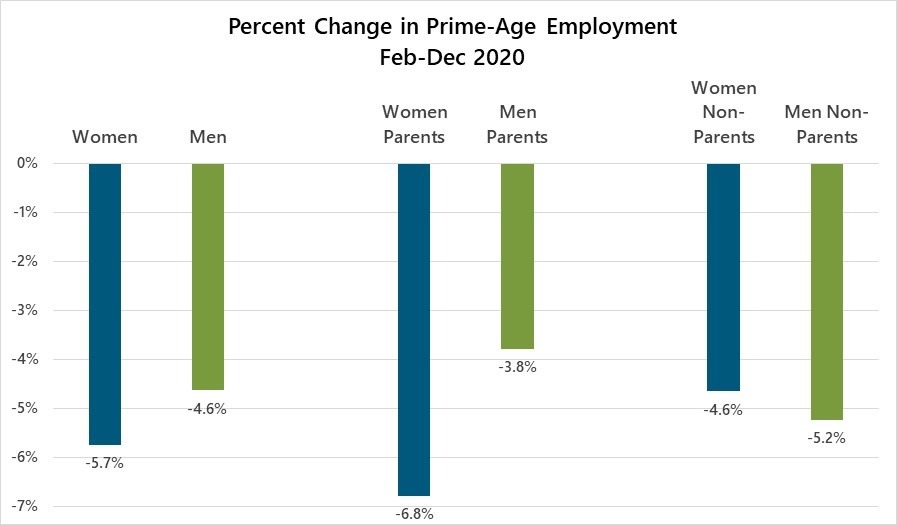

What is interesting about this gender gap is it’s less about gender alone and more about the intersection of gender and parenthood. To be more specific, for prime-age women and men who are not parents, the data show very similar rates of change in employment. If anything, employment of non-parent women fell less than that of men. It’s only for women and men who are parents – also known as moms and dads — that this gap is quite apparent. This reveals one of the ugly truths of the pandemic: it seems many more women than men had to choose between being the primary caregiver for their children and being employed.

The chart below depicts the evidence. It shows changes in employment from February to December for all prime-age women and men, and then separately based on parental status. As the chart shows, employment of moms fell 6.8 percent, a substantially more severe drop than the 3.8 percent decline in employment of dads. For non-parents, employment of women fell less than that of men.

Another way to look at these outcomes is, as a result of the pandemic, a mom is almost 1.8 times more likely than a dad to no longer be employed. Moreover, if moms had the same labor market outcomes as non-parent women or dads, approximately 600,000 more moms in the US would currently be employed. There are two likely reasons for these worse outcomes for mothers. One is obvious – as the pandemic caused schools and childcare services to shut down, generally speaking, more moms took on more of the primary responsibility of caring for children. Survey evidence supports this explanation[3]. The second reason is occupational mix – women are more likely to be employed in occupations requiring physical proximity[4] and less likely to be in occupations with ability to telecommute[5]. Occupations more dependent on physical proximity and less disposed to telecommuting were more likely to be cut during the pandemic.

The encouraging news is help is on the way via a mix of organic economic growth, continued monetary stimulus, and a new fiscal package aimed at providing support to both working and unemployed mothers. The State has undertaken a number of initiatives to support the childcare sector and families in need of childcare assistance in this critical moment, including increased investments in childcare, waiving parent co-pays in the State’s childcare subsidy program, offering grants to childcare providers and providing tuition support for school-aged supervision. And there are private sector initiatives, such as Golden Seeds, which seeks to support women entrepreneurship through pooling and distribution of financial and human capital. The help is sorely needed, not only to provide current economic relief but to keep this from becoming a long-term economic problem for mothers.

The fact is, the longer someone is out a job, the harder it can be to get another one or to make up for lost income, so time is of the essence. This phenomenon is due to what economists call labor “scarring.” From an economics point of view, the key concept at play is depreciation of human capital. In essence, the longer a person is out of work, the more that person’s skills and knowledge – the human capital – depreciate. If labor compensation is a return on human capital, depreciated human capital returns lower compensation. In other words, your lifetime wages are permanently set back by a scarring effect, and there have been many studies done to show this effect is real. In fact, even in the “women-friendly” labor market in Sweden, research shows the length of time out of the labor force for parental leave is associated with negative effects on labor market outcomes and career pathways[6]. Let’s hope the scarring is kept to a minimum and more women are quickly reabsorbed into the workforce.

Women-Owned Businesses in New Jersey – A Brief Look at the Landscape

This section provides a basic overview of the data on women-owned businesses in New Jersey. Based on the most recent data available, there are approximately 300,000 businesses in New Jersey owned by women.[7] This is the sum of women-owned businesses with and without employees (known as “employer”and“non-employer”firms,respectively).

The data show women-owned firms make up about 18 percent of all employer firms and about 38 percent of non-employer firms. Both shares have increased over the past 10 years. In 2007, 15 percent of all employer firms and 31 percent of all non-employer firms in New Jersey were women-owned.

Clearly, women ownership has a larger stake in the nonemployee landscape. And there are some standout industries. For example, as seen in Table 2, women own more than 50 percent of all non-employer firms in health care and social assistance, educational services, and administrative and support services. Within the employer firm landscape, women own the greatest share of firms in educational services (36 percent).

Table 1 – Women-owned Employer Firms

Industry | Number of Women-Owned Employer Firms | Women-Owner Share of Firms in the Industry |

Total for all sectors | 34,130 | 18.20% |

Health care and social assistance | 5,401 | 24.80% |

Professional, scientific, and technical services | 5,132 | 19.20% |

Other services (except public administration) | 4,582 | 30.90% |

Retail trade | 4,219 | 18.80% |

Accommodation and food services | 3,728 | 19.50% |

Administrative and support and waste management and remediation services | 1,874 | 16.20% |

Construction | 1,832 | 8.40% |

Educational services | 1,344 | 35.90% |

Real estate and rental and leasing | 923 | 12.60% |

Manufacturing | 912 | 13.00% |

Transportation and warehousing | 822 | 12.40% |

Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 743 | 22.40% |

Finance and insurance | 662 | 10.50% |

Information | 303 | 14.70% |

Industries not classified | 44 | 15.80% |

Management of companies and enterprises | 27 | 3.60% |

Table 2 – Women-owned Non-employer Firms

Industry | Number of Women-Owned Non-Employer Firms | Women-Owner Share of Firms in the Industry |

Total for all sectors | 266,000 | 37.80% |

Professional, scientific, and technical services | 44,000 | 37.90% |

Other services (except public administration) | 39,000 | 51.00% |

Health care and social assistance | 37,500 | 70.80% |

Real Estate and rental and leasing | 29,000 | 29.00% |

Retail Trade | 25,000 | 49.50% |

Administrative and support and waste management and remediation services | 25,000 | 55.60% |

Educational services | 15,000 | 60.00% |

Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 14,500 | 37.70% |

Transportation and warehousing | 13,500 | 17.00% |

Finance and Insurance | 5,300 | 23.00% |

Construction | 4,700 | 8.60% |

Accommodation and food services | 4,700 | 44.80% |

Wholesale Trade | 3,500 | 26.90% |

Information | 3,300 | 31.40% |

Manufacturing | 2,000 | 31.30% |

Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | 400 | 20.00% |

Utilities | 70 | 17.50% |

Key Indices for Gender Inequality Globally

Gender gaps manifest themselves in a wide range of measures well beyond those concerning economic inequality. Other ways to view such gaps include political representation, healthcare, education, and societal issues, to name a few. Dealing with such a wide array of variables can be somewhat overwhelming, which is why many institutions create indices to organize multiple factors and simplify them in the form of a single score. Here we are looking at the United Nation’s Global Inequality Index (GII) and the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index (GGI) to see two examples of how gender inequality is measured and where the United States ranks.

United Nations Gender Inequality Index (GII) | US Metrics | U.S. Rank (out of 162) |

United States’ Overall Rank | 46th | |

Maternal Mortality Ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births) (2017) | 19 | 56th |

Adolescent Birth Rate (2015-2020) | 19.9 | 57th |

Percent of Seats held by Women in Parliament (2019) | 23.7 | 66th |

Percent of prime-age population with at least some secondary education (2015-2019) | 96.1 | 20th |

Labor Force Participation Rate (%) (2019) | 56.1 | 64th |

World Economic Forums’ Gender Gap Index Factors (GGI) | U.S Rank (out of 153) |

Overall Rank | 53rd |

Economic Participation | 26th |

Educational Attainment | 34th |

Health and Survival | 70th |

Political Empowerment | 86th |

The UN’s GII ranks 162 countries on five distinct measures of gender equality: infant mortality, adolescent birth rate, seats held by women in parliament, the percentage of women with some secondary education, and the labor force participation rate. The United States has an overall ranking of 46th out of 162 countries. The US would fall lower were it not for the US’s secondary education rate ranking 20th. The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) GGI is designed to account for gender disparities in economic participation, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. On this measure, United States ranks 53rd out of 153 countries. Where the US shows considerable weakness is in health and survival, and political empowerment. Since the last time the GGI was published in 2018, the United States ranking fell by two places, caused primarily by a decline in labor force participation. The WEF emphasizes that the 21.7 percent non-male executive participation rate and the 23.7 percent non-male parliamentary participation rate are critical factors in improving the United States’ gender gap in the future.

It is evident through both of these indices that the United States is lagging on the global stage in multiple gender measures. A focus on economics, healthcare, and education is essential to acknowledging and solving the problem that women and non-binary individuals face in our country.

[1] Measured at a 3-month moving average to reduce month-to-month noise in the data

[2] Lofton, Olivia, Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau, Lily Seitelman. “Parents in a Pandemic Labor Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2021-04. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2021-04

[3] Zamarro, Gema and Maria Jose Prados, “Update on Gender Differences in the Impact of COVID-19,” CESR report, University of Southern California December 2020.

[4] Mongey, Simon, Laura Pilossoph, and Alex Weinberg, “Which Workers Bear the Burden of Social Distancing Policies?,” Working Paper 27085, National Bureau of Economic Research May 2020.

[5] Alon, Titan, Matthias Doepke, Jan Olmstead-Rumsey, and Michele Tertilt, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality,” Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers, 2020, 4.

[6] Aisenbrey, S., M. Evertsson, & D. Grunow. “Is There a Career Penalty for Mothers’ Time Out? A Comparison of Germany, Sweden and the United States.” Social Forces, 88(2), 573-605, 2009.

[7] 2018 Annual Business Survey; 2017 Nonemployer Statistics by Demographics.

Related Content

April 29, 2025

NOTICE OF MEETING CANCELLATION - NEW JERSEY GREEN BANK BOARD MEETING

Please be advised that the Board Meeting for the New Jersey Green Bank scheduled for May 8, 2025, is hereby cancelled.

April 29, 2025

NJEDA to Host In-Person Resource Fair During National Small Business Week

TRENTON, N.J. (April 29, 2025) – In celebration of National Small Business Week, the New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA) will host an in-person “Show Me the Resources” fair to highlight key state resources available for small business owners and entrepreneurs.

April 28, 2025

In Observance of Earth Month, NJEDA Announces More than $4.3M to Support Green Economy Workforce

TRENTON, N.J. (April 28, 2025) – In celebration of Earth Month, the New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA) announced it recently approved four applications under the NJ Green Workforce Training Grant Challenge, totaling over $4.3 million in funding.