By Richard Kasmin, NJEDA Chief Economist

By Richard Kasmin, NJEDA Chief Economist

Innovation is an essential ingredient for economic growth. But what exactly do we mean when we speak of innovation? At its core, it’s economic evolution – the process of taking what has been discovered and applying those discoveries to create improved ways of using finite resources to get things done.

Innovation can be in the form of a process or a product. For example, learning ways to use available technologies to produce things more quickly, or cheaper, or with less energy consumption are types of innovation.

The creation of something as seemingly simple as a pencil was the product of uncountable innovations over hundreds of years. Think of what it takes to produce a pencil: the raw materials, the ability to arrange for those resources to come together, and the labor and machinery required to make a pencil. And that’s to say nothing of getting the pencil to the market, where the value of the product is finally realized.

The big differences between the pencil and what we consider more modern examples of innovation can be measured on two dimensions: time and value. In terms of time, we’re talking about past and present. It’s difficult, in the year 2020, to consider a pencil the product of innovation. DNA engineering, by contrast, is happening now, and it seems almost magical in terms of potential economic impact. In terms of value, different innovations have different economic impacts. The pencil certainly created economic value, but when compared to the potential benefits of DNA engineering in terms of health care, the economic benefits of a pencil seem small.

Many state policy makers understand the value of innovation in terms of economic growth and increasing standards of living, and they are implementing various policies to encourage innovation. No matter what the innovation, there is one thing they all have in common – risk. Innovators and the people who invest in innovators take risks. Thus, this is where policy makers generally focus their attention – how to mitigate the cost of taking risk to encourage innovation investment.

The Angel Tax Credit

One such policy we have in New Jersey to encourage investment in innovation is the Angel Tax Credit. As the name suggests, The Angel Tax Credit provides tax credits to so-called angel investors against qualified investments in New Jersey technology and life sciences businesses. It is meant to boost access to funding for early-stage businesses engaged in technology and life sciences. Moreover, assuming the tax credit does encourage investments that would not have otherwise occurred, it increases the size of the innovation economy and helps to build a robust angel investment community.

Angel investors are a special breed of investors. More than just funds, angel investors also tend to invest their time and expertise into the firms they support. They fund early-stage entrepreneurs and often serve as mentors or outside directors of startups.

Research indicates angel investors have significant positive effects on the firms in which they invest. As evidence, a study conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research showed firms with high angel investor interest were more likely to succeed than firms with low angel interest (Fig 1). The researchers concluded, “Firms that attracted a high level of interest among angel investors were more likely to grow, issue patents, win new rounds of funding, and have a successful exit from the startup phase.”

Figure 1 – The Positive Impact of Angel Investing

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research

In 2020, the size of the tax credit will rise from 10% to 20% of qualified investments. Moreover, there will be an additional 5% credit for investments made in firms located in Opportunity Zones and minority- or women-owned firms.

Increasing the size of the tax credit makes sense. To understand the right size of the incentive, one must consider the motive to invest in the first place. Angel investment are high risk investments – the investor is making an investment in a firm at its earliest stages of existence. Firms during this time are more likely to be engaged in research and development and are likely to have little-to-no revenue. Thus, these firms have no clear market value – you can’t really assess economic value without generating some revenue. Thus, the value of these firms is based more on a bet for what it will be worth once their products hit the market. And a lot must go right for all that to happen.

Thus, these tend to be very high-risk investments where investors are making a bet to hopefully generate multiples of their original investment. As such, a larger incentive is likely necessary to alter investment decisions, which is what incentives like the Angel Tax Credit are meant to do.

Angel Tax Credit History

Since the program’s inception in 2013 through 2019, the NJEDA has approved around 1,400 Angel Tax Credit applications for almost $600 million in investments in around 90 New Jersey-based businesses. Looking at the sector destinations of those investments, 45% went to life sciences companies and 55% went to technology companies (of which, 14% went to clean technology companies).

The two charts below show flows of approved applications and investments broken down into three sector destinations — clean technology, life science, and other technology. Figure 2 depicts applications by year for the life of the Angel Tax Credit program. Figure 3 depicts the investment flows for which those tax credits were applied. Focusing on the last four years, approved applications have averaged around 240 per year for an average of around $120 million in investments per year.

Figure 2 – The Number of Applications Per Year

Figure 3 – Investments Supported by Angel Tax Credits

The Geography of Venture Capital and Angel Tax Credits

One question we might ask is, where do we see venture capital flows in New Jersey, and how representative of geographic coverage in the state are Angel Tax Credits? To answer the first part of that question, we mapped data from Crunchbase, a web-based platform that provides data on the locations of headquarters who received venture capital funding (2011 to present). As the map below shows (Figure 4), there is evidence of what looks like a Start-Up Corridor, with hot spots around Jersey City and Princeton. There are some concentrations of firms along the shore and near Camden. When we look at the locations of headquarters for firms that benefitted from angel tax credit investors (Figure 5), we see some similar hot spots in and around Jersey City, Newark, New Brunswick, and Princeton. Most all activity is in the northern portion of the state, north of 195. It may be worthwhile to consider whether more can be done to expand the geographic coverage of the Angel Tax Credit outside some of the current hotbeds to attempt to expand the venture capital ecosystem.

Fig. 4 – VC in New Jersey

Fig. 5 – Angel Tax Credit HQs

Underrepresented Communities

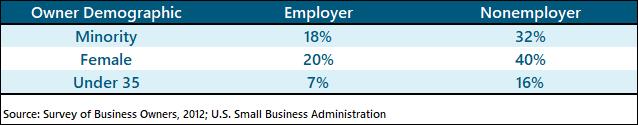

As noted earlier, the new iteration of the Angel Investor Tax Credit will provide bonuses for investments made in opportunity zones or firms that are minority- or female-owned. That begs the question, what evidence do we have firms in such categories require more attention?

According to a recent survey by DiversityVC and RateMyInvestor, nationwide only one percent of venture-backed founders are black and less than two percent are Latinx. Clearly, black and Latinx populations lack access to venture capital.

Female-owned firms – companies that are both solely owned or owned in partnership with male owners – do not fare much better. In the eleven years of data released by Pitchbook (2008-2019), female-owned firms in New Jersey generated 176 deals capturing $769 million in venture capital flows. The flow during this period accounted for approximately 13 percent of deals and 9 percent of capital flows. Clearly females are underrepresented in this corner of the economy.

Yet, as depicted in Figure 6, the data shows female-owned firms in New Jersey are seeing a growing share of flows. Looking at the linear trend (depicted in the dotted lines), since 2008, the share of deals and flows in New Jersey going to female-owned firms has increased approximately one percentage point per year. In 2008, female-owned firms accounted for approximately 7 percent of deals and just 4 percent of capital in New Jersey. In 2019, those shares rose to approximately 23 percent and 14 percent, respectively.

Figure 6 – The Share of Venture Capital Flows Going to Female-Owned Firms

In conclusion, policymakers are focused on supporting the growth of innovation ecosystems for good reason – innovation is instrumental for economic growth and increased standards of living. Given the risk commensurate with angel investing, increasing the size of tax credit should incentivize increased investment and encourage growth of New Jersey’s innovation ecosystem. Furthermore, the evidence shows women- and minority-run firms have historically faced challenges in accessing capital, and the focus of the Angel Investor Tax Credit on these populations should lend needed support.

For more information on the Economist’s Corner, or to view the archive of Economist’s Corner postings, please visit www.njeda.gov/economistcorner.

.jpg.aspx?width=750&height=440)

.jpg.aspx?width=750&height=440)

.jpg.aspx)

.jpg.aspx)

.jpg.aspx?width=750&height=440)

.jpg.aspx?width=750&height=420)